Bitter Sweet Symphony

Late 1980s/early 1990s

The knots in his stomach tightened again. Ehimen wished he were invisible so teachers would stop asking him to read or answer questions, sparing him from the derision of his classmates, who seized every opportunity to mock his American accent, his responses, or both. It was why he dithered before answering ‘papaya’.

As expected, the class exploded with laughter, and though he’d anticipated their reaction, Ms Ajala’s expression confounded him. Ehimen sensed she might not have heard him correctly and repeated himself. Again, his classmates roared, sending a heatwave of embarrassment that turned his face an ixora red. Later, he would learn the Nigerian word for the fruit is paw-paw, but until then, he sat in mortified silence, praying the floor would open and swallow him up. He hated his new school.

The teacher rapped her cane on a desk, threatening to discipline the entire class if they didn’t quiet down.

‘Can you describe what it looks like?’ asked Ms Ajala, her large, brown eyes considering him with interest.

His stomach heaved at the focused attention on him, at the dread of inciting another episode of ridicule, one that usually spilt into break time and ran into the following day. Casting his gaze to the floor, Ehimen slowly shook his head. But Ms Ajala, unrelenting in her quest for an answer, persisted.

‘You can’t describe the fruit?’ There was a note of puzzled disappointment in her voice.

Again, Ehimen shook his head, prompting a scattered round of sniggering that dissipated when Ms Ajala called on his seatmate to name a food rich in vitamin C.

‘Mango,’ she answered smugly.

Why hadn’t he said that, Ehimen thought, silently berating himself. Not that it would have made a difference. Every word out of his mouth, even the way he pronounced his name, attracted jibes and laughter like vultures to a carcass.

Later that day, the Backbencher Boys cornered him in the toilet as he was washing his hands. The clique who sat at the back of the classroom. Their imposing heights struck such a menacing image in the minds of fellow pupils that no one dared pick fights with them.

The ringleader, a sturdy boy with dimples, let out a snigger, triggering a marathon of name-calling that Ehimen could recite in his sleep like the Nicene Creed: Yellow garri, Marmalade, Miranda boy, Fanta, Yellow papaya, the last one a new addition to the roll-call of abuses. The boys cracked up at their own jokes, save for one. He was watching the scene in silence. His subdued presence intrigued Ehimen, because just last week he’d led the taunts.

‘Papaya, papaya,’ they hooted in crude American accents.

‘Why don’t you say your name again?’ jeered one of the boys amid a torrent of laughter.

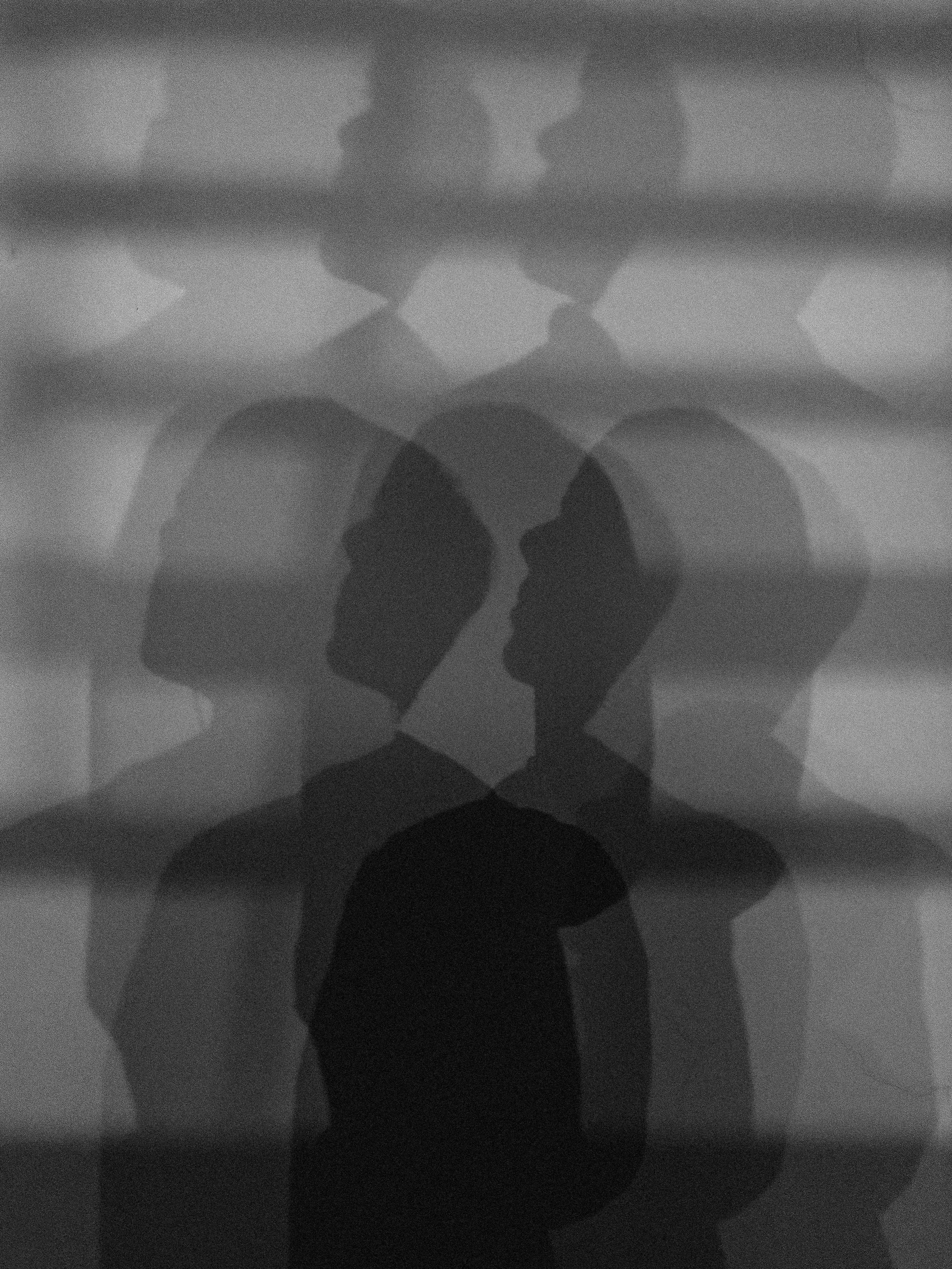

All the while, Ehimen kept his head down, trying mightily to avoid the boys’ reflections in the mirror. The last time their eyes connected, they took it as a cue to manhandle him. He’d fought back, but was outnumbered eight to one, and knew repeating the daredevilry would definitely land him in the headmistress’s office again, with another ripped shirt. So he stilled himself like a cockroach, playing dead, waiting for the ridicule to wane, certain the sea of idiocy would ebb if he pretended their harsh words were nothing more than a light wind wafting over the boughs of a mahogany tree.

But then a voice tore through the melee, abruptly silencing everyone. Ehimen couldn’t resist his curiosity. His gaze crept up to the mirror in search of the source. It was the boy who’d been quietly observing the fracas.

‘We’re not pleasing God,’ he said, his voice strong and uncertain at once.

Stunned by the revolt from one of their own, the Backbencher Boys stood mute and unmoving, until the ringleader, determined to save face, walked over and stood nose to nose with the rebel. The boy stared right back with a glare, daring him to do his worst. For a beat neither boy stirred, each waiting for the other to back down. A wry, mysterious grin broke through the ringleader’s lips, then, without a word, he strolled out of the toilet. The rest of the gang followed, slinking out one after another.

Years later, Ehimen would liken the scene to the craven retreat of the Pharisees from their plot to stone the adulterous woman, joking that in his case he had been without sin. The boy, meanwhile, would confess to Ehimen that he had been motivated by the homily on the Good Samaritan from that week’s Sunday mass. The priest had exhorted his congregants to ask themselves how Jesus would react in a given situation, and should imitate him if they were to please God.

Alone finally, the tall boy said, ‘Do you want to play table tennis with me?’ He was smiling a genial smile.

Ehimen considered him for a beat, mulling the boy’s sudden transition from foe to friend, wondering whether his offer was genuine. Something about his demeanour made him think so. Besides, he was tired of spending his break sitting alone in class, so he nodded.

Read the rest of the story on Johannesburg Review of Books.

You May Also Like